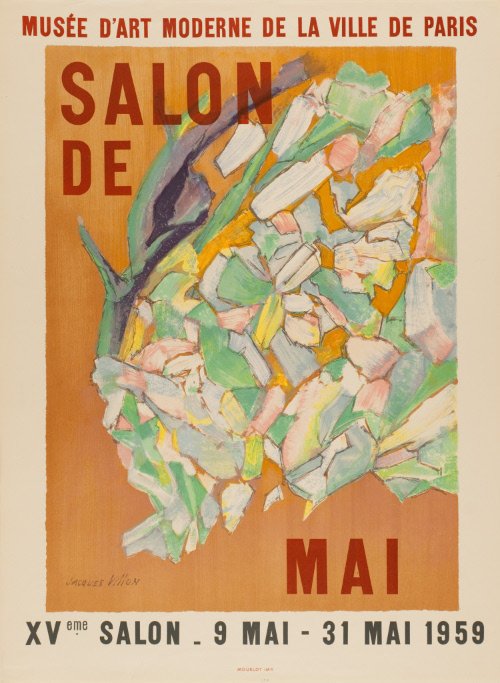

Jacques Villon

French painter and printmaker, 1875–1963

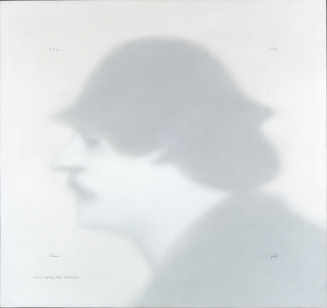

In large part to make a break with his dependence on commercial illustration, Villon in 1906 moved to Puteaux, a suburb of Paris, where his brother Raymond and František Kupka became close neighbours. Devoting increasingly more time to painting and independent printmaking, he ceased entirely to make satirical cartoons by 1910 and in that year moved definitively from an expressionistic drawing style to an interest in volumes and planar structure; this shift is evident in a series of three prints (one drypoint and two etchings) entitled Renée (1911; see 1989 exh. cat., pp. 71–3) and in a dramatic portrait of Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1911; Paris, Pompidou). At this time he and his brothers became friendly with Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Henri Le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger and Robert Delaunay, who in showing their work together at the Salon des Indepéndants in 1911 had caused a furore as proponents of Cubism. The circle of artists who made regular visits to Villon and Duchamp-Villon expanded rapidly, and many of them made contributions to the Maison Cubiste displayed at the Salon d’Automne in 1912, an attempt to extend the innovations of Cubism into the realm of life through architecture and the decorative arts, spearheaded by Duchamp-Villon and the French painter André Mare (1885–1932). Villon designed a tea service (priv. col., see 1976 exh. cat., pp. 51–2) for this complex. The same group of artists formed the core of an exhibition held in October 1912 entitled Salon de la Section d’Or, the widest manifestation of artists touched by Cubism. The term was bestowed by Villon, who had been reading the writings of Leonardo da Vinci, and it suggests the respect for proportion and harmonic structure that now characterized his art; unlike colleagues such as Juan Gris and Metzinger, however, Villon at that time did not regularly employ the formula of the golden section as a structure for all his compositions.

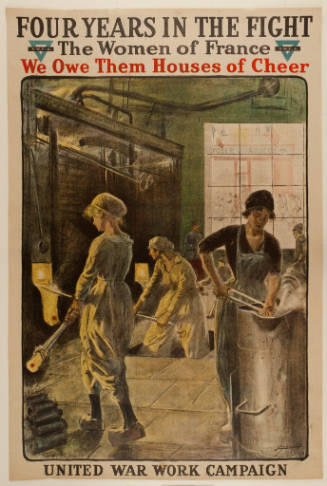

Villon’s art and reputation were in full flower at the outbreak of World War I in 1914. By 1916 he was transferred from an infantry regiment serving at the front to a camouflage unit at Amiens. There is reason to believe that the two years during which he worked at camouflage caused him to study color theory, especially M. A. Rosenstiehl’s Traité de la couleur (Paris, 1913). A new and systematic use of color is visible in the austere and pure abstract paintings produced by Villon just after the war. In works such as Nobility (1920), Joy (1921; both priv. col., see 1976 exh. cat., pp. 98–9 and 102) and the Colour Perspective series (e.g. Colour Perspective, 1921; New York, Guggenheim) Villon expanded his compositional approach. This now involved careful preparation and systematic distortion derived from the techniques of the etcher, including reversals and rotations, with the experience he had gained through camouflage of the deceptions of color. Villon insisted that a visual idea be incorporated into a canvas from its moment of origin, with the object only as a starting-point and its forms represented by planes adjusted to the proportions of the picture. Along with Gleizes, he was one of the few French artists who explored abstraction during the early 1920s, for example in The Jockey (1924; New Haven, CT, Yale U. A.G.), but again the thrust of his painting activity was interrupted. The Bernheim-Jeune gallery in Paris, prompted by a group of their exhibiting artists who knew of Villon’s skill as a printmaker, approached him with the idea of making a series of reproductive prints after established modern artists such as Manet, Renoir, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, Braque, André Derain, Vlaminck, Raoul Dufy and Bonnard. Between 1922 and 1930 Villon made about 40 such color aquatints, at first fulfilling the requests of the gallery but after 1927 asserting his own choices; these included family members Marcel Duchamp, Suzanne Duchamp and his former brother-in-law Jean Crotti and friends such as Gleizes, Metzinger and Mare.

In the summer months, when not harnessed to the Bernheim-Jeune project, Villon continued to work for himself. He concentrated especially on drawing, working from life (e.g. Seated Woman, pencil, c. 1931; priv. col., see 1976 exh. cat., p. 124) from the sculptures of Duchamp-Villon (who had died in 1918), or from motifs he had developed much earlier. During these years he brought to perfection the fluid graphic style most associated with his drypoints and etchings, a linear grid formed by a dense network of energetic diagonals intersecting with varying degrees of light intensity, depending on the addition or subtraction of verticals and horizontals. Papers on a Table (1931; Paris, Bib. N.) is a notable example of this style, which was a considerable influence on contemporary European artists ranging from Giorgio Morandi to Marcel Gromaire. Villon returned to painting in another burst of activity during the early 1930s. Prodded by Gleizes, he took part in the activities of Abstraction–création; although these works were all derived from subjects that had their origins in common visual experience, the emphasis on planar construction against which Villon played off apparently free linear motifs produced the most lyrical abstract paintings of his entire career. These pictures are carefully governed by systems of mathematical proportion in accord with highly generalized titles, such as Architecture (1931), Gaiety (1932) and Space (1932; all priv. col., see 1976 exh. cat., pp. 132, 133, 135), which he reserved for the most ambitious of his accomplishments.

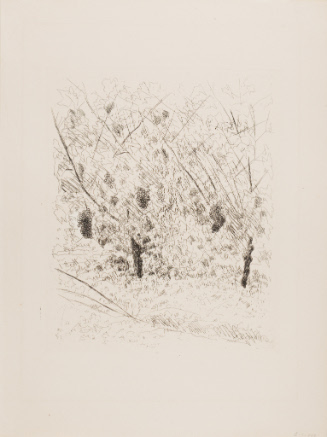

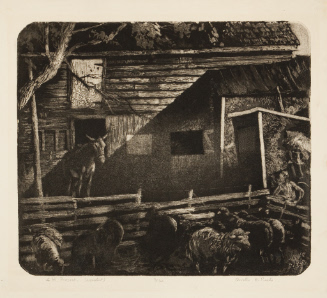

Shortly before his death, Villon recalled the 1930s as a time in which he worked in almost complete isolation, ignored or regarded as a marginal figure. He spent most of World War II living in the country, either at the home of André Mare’s wife in Bernay or at the farm of her daughter, Mme Mare-Vené, at La Brunié in the Tarn. Having become interested in landscape only in the mid-1930s during a trip to Provence, Villon now alternated intimate pictures of farm life (e.g. Kitchen-garden at La Brunié, 1941; Cleveland, OH, Mus. A.) with abstract and sometimes grandiose landscapes based on a synthesis of the entire high plateau region from Toulouse to Albi. In painting the Bridge at Beaugency (1944; Paul Mellon priv. col., see 1976 exh. cat., p. 152) he evoked a traditional musical round (‘Orléans, Beaugency, Notre Dame de Bercy’) familiar to all French children. Works such as the Three Orders (1944; Richmond, VA Mus. F. A.), while consistent with his interest as a Cubist in subjects with epic resonance, assumed a special significance after World War II because they showed a resilient French past in spite of the Occupation. Louis Carré took Villon into his gallery in Paris, giving him his first one-man show since 1934. Villon very quickly re-established his reputation and his influence on a younger generation. He won numerous prizes during this period: the Grand Prix de la Gravure at the Exposition Internationale in Lugano (1949); first prize at the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh (1950); Grand Prize for painting at the Venice Biennale (1956); and the Grand Prize for painting at the Exposition Internationale in Brussels (1958). In the course of a long and productive life, Villon illustrated or contributed original prints to 27 books, of which only two, Architectures (Paris, 1921) by Louis Süe and André Mare and Poésies (Paris, 1937) by Pierre Corrard, appeared before World War II. His editions of Paul Valéry’s French translation of Virgil, the Bucoliques (Paris, 1955), and Jean Cocteau’s French translation of Hesiod, Les Travaux et les jours (Paris, 1962), and François Villon’s Grand Testament (Paris, 1963) are among the most admired of his later illustrated books. In 1963, the year of his death, he was elected Grand Officier de la Légion d’honneur.

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

- Puteaux

- Damville

American painter, sculptor, 1901–1980

French etcher and illustrator, 1872–1941

American painter, sculptor, and printmaker, born 1930

French painter, draftsman, and printmaker, 1884–1974

Swiss artist and illustrator, 1859–1923

American painter, printmaker, 1884–1968

American painter, illustrator, and engraver, 1859–1950