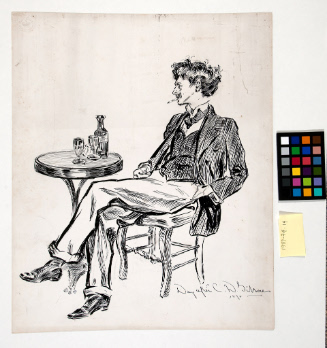

Harry Fenn

American painter and illustrator, 1837–1911

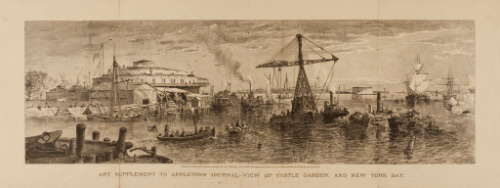

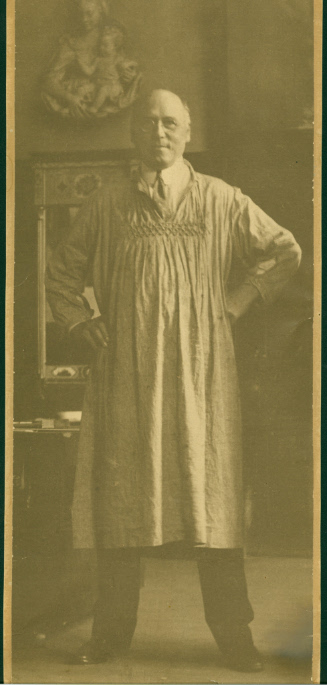

In 1870, the weekly Appletons’ Journal introduced Picturesque America, a magazine series subsequently published as a two-volume book. Initially the sole illustrator for the series, Fenn contributed views of landscapes, cities, and suburbs that educated readers would have recognized as exemplars of the picturesque aesthetic. His cascading waterfalls and towering mountains proved that America had the equivalents of European scenery, while his romantically weathered buildings showed that the country also had charming ruins. His close-up views of detailed rock formations coincided with current geological investigations; his distant bird’s-eye perspectives intersected with the public’s fascination with stereography and photography. The popular and critical success of Picturesque America generated Picturesque Europe and Picturesque Palestine, which kept Fenn at work abroad from 1873 to 1880. In all the Picturesque books, Fenn enlivened some of his pages with vignette-style irregularly shaped images fitting into and around the text, a harbinger of the Aesthetic movement’s attention to harmonious book design.

Back in the United States by 1881, Fenn took up assignments for various publishers, while regularly exhibiting his watercolors. He illustrated texts ranging from reassessments of the Civil War to studies of American architecture, designed promotional materials for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, and created photography-based images of the Spanish-American War and events in China. He often adapted the subjects of his Picturesque illustrations, and was one of the illustrators for a ten-volume Picturesque California and the Regions West of the Rocky Mountains.

In 1897, a minority of critics judged an edition of Tennyson’s In Memoriam, marketed as ‘exquisitely illustrated by Harry Fenn’, as ‘old-fashioned’. By 1903, one writer admired Fenn’s entry in the annual American Watercolor Society, but added that ‘one almost never nowadays sees bark and lichens painted with such fidelity’. Fenn’s 1904 illustration of Utah’s Augusta Bridge shows his skill in adopting the more impressionistic and less detailed approach popular at the time and more suitable for the color half-tone process. But changing tastes in art and illustration and publishers’ increasing use photographs led to fewer commissions. Still, the indefatigable Fenn illustrated an article on gardens for Century just weeks before his death in 1911.

Fenn’s career makes evident the link between illustration and current American trends and attitudes during a period driven by ‘illustration mania’. In the second half of the nineteenth century, an increasingly literate public eagerly consumed publications that—as one commentator noted—‘improve the taste, instruct the eye…and touch the heart.’ Fenn’s illustrations intersected with developments in science, notions about history and religion, the economics of publishing, and changing views of American art, especially wood engraving and watercolor. Fenn’s various methods and styles demonstrated that he was remarkably adaptable in adjusting to shifting tastes and developing printing technologies.

Fenn created his approximately one thousand original works of art—many of which have not survived— in watercolor and ink on paper, designing them for the mass-reproduced pages of books and magazines. He recorded a world of American landscapes, city life, and culture, within the context of an emerging national identity. His work also revealed the wider world beyond America’s borders, one that many readers would see only his illustration. Later critical denigration of illustration contributed to the eclipse of Fenn’s reputation.

Adpated from Sue Rainey, Creating a World on Paper: Harry Fenn’s Career in Art, Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013; and review in Print Quarterly, p. 329, No. 3, vol. XXXI (2014), by Mary F. Holahan

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

- Montclair

- Surrey

- artists

- male

English painter and printmaker, 1799–1883

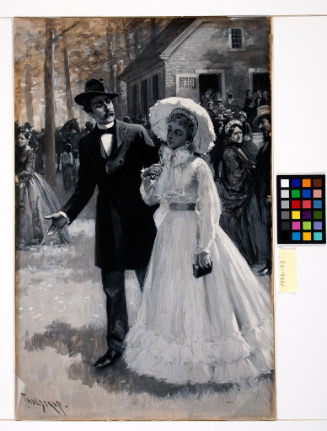

American painter, illustrator, and printmaker, 1858–1932

French etcher, engraver, and draftsman, 1592–1635

American painter and illustrator, 1883–1960

French printmaker, painter, sculptor, 1832–1883

English caricaturist and watercolorist, c.1756–1827

American illustrator and painter, 1867–1944

American artist and illustrator, 1848–1930

American painter and illustrator, 1870–1966

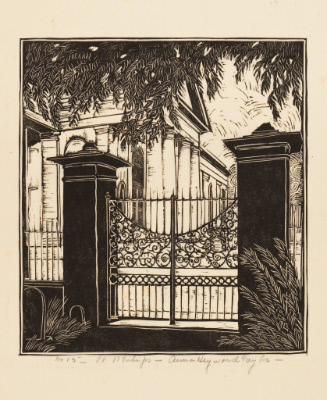

American painter, craftsperson, decorator, and block printer, 1879–1956

British painter, etcher, and draftsman, 1886–1966